Rethinking U.S. Healthcare: The Case for a Single-Payer System

The U.S. healthcare system represents a paradox: despite the country's unparalleled wealth and technological sophistication, its overall performance lags behind that of many other developed nations. This apparent failure is not due to inadequate spending - America invests about $4 trillion annually in health care—but rather is rooted in structural inefficiencies created by a privatized insurance framework. The focus of this paper is to examine how the private insurance model has distorted American health care and to propose a shift to a single-payer system through three essential reforms: consolidating bargaining power to negotiate lower prices, eliminating redundant administrative bureaucracy, and realigning health care priorities by removing the profit incentive from essential care decisions.

At its core, the U.S. healthcare system's dependence on a vast web of private insurers creates a heavy administrative drag on providers. Billing and claims processing alone now total some $768 billion each year, a burden driven by fragmented negotiations and ever‑shifting fee schedules (Woolhandler and Himmelstein). That fragmentation shows up in striking examples—charges for an uncomplicated birth in California can swing ten‑fold, even when patient profiles are virtually identical (Hsia et al.). All this complexity translates into far higher overhead: private plans pour 12.4 % of every premium into administration, compared with just 2.2 % under Medicare (Woolhandler and Himmelstein). To make matters worse, hospitals routinely pad prices to cover an estimated $35 billion in unpaid bills each year (American Hospital Association). And because private insurers negotiate rates above Medicare's fixed schedule, the cost of identical services balloons: simply applying Medicare's fee structure nationwide would shave hospital charges by 5.54 % and clinical fees by 7.38 %, unlocking over $100 billion in annual savings (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). By moving to a unified, single‑payer billing framework, solve this,, streamline interactions between providers and payers, and deliver meaningful cost relief—without sacrificing the quality of care patients deserve.

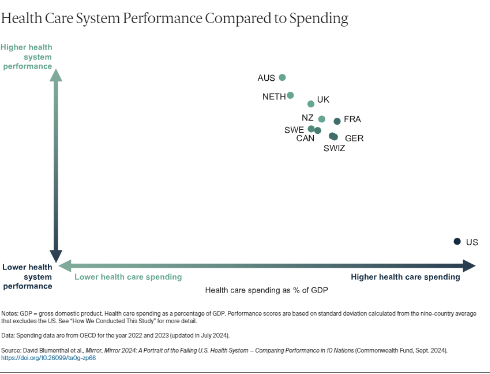

The U.S. health insurance industry's skewed profit motive inflicts tangible harms on patients: since the Affordable Care Act's passage, America's five largest insurers have amassed over $371 billion in profits—more than forty percent of which went to UnitedHealth Group—while denying nearly one in three claims, forcing many families to delay or forgo necessary care (Santoro). At the same time, the average cost of childbirth in the United States reaches $18,865, leaving new parents responsible for roughly $2,850 of that bill and often saddling them with crippling medical debt (Ceron). Beyond financial strain, lack of affordable coverage exacerbates social ills: research shows that states expanding Medicaid under the ACA experienced a 5.3 percent reduction in violent crime—as increased access to mental health and substance‐use treatment and relief from medical debt lowered factors that contribute to criminal behavior (Vogler). The CommonWealth Fund cautions that "despite spending vast amounts for generally poor results—the very definition of a low‑value health system," the United States remains the only high‑income nation without universal coverage, leaving 26 million Americans uninsured and nearly a quarter underinsured, "facing high deductibles and copayments that reduce the effectiveness of their insurance in assuring access to needed care" (Blumenthal et al.). The report further explains that U.S. health care, with "thousands of health insurance products, wide variation in benefits, and complex utilization management policies," becomes "a nightmarish maze for patients and care providers alike," ranking second‑to‑last in administrative efficiency (Blumenthal et al.).

By pooling all public and private purchasers into a single entity, a single‑payer system wields far greater leverage in negotiating with drug manufacturers and providers. In Canada, government price negotiations through the pan‑Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance keep per‑capita drug spending at roughly half the U.S. level—about $600 versus $1,200—thanks to unified bargaining (Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development). Likewise, Commonwealth Fund analysts note that the U.K.'s National Health Service routinely secures oncology therapies at discounts up to fifty percent off American list prices (Commonwealth Fund). Building on these lessons, the Inflation Reduction Act empowers Medicare to negotiate prices for ten high‑cost Part D drugs beginning in 2026—projected to save the program $6 billion in 2026 alone and reduce beneficiary out‑of‑pocket costs by $1.5 billion that year (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). Those negotiation savings complement the new $2,000 annual cap on Part D out‑of‑pocket spending, a reform estimated to spare seniors hundreds of dollars each (Kaiser Family Foundation). Critics warn that lower revenues could dampen pharmaceutical R&D, but recent evidence finds no slowdown in new drug approvals among nations with centralized price controls (Younkin). Moreover, negotiated price restraints can coexist with innovation "when paired with targeted incentives and public–private partnerships" (Commonwealth Fund).

As part of this research paper, I interviewed Dr. David Himmelstein—a co-founder of Physicians for a National Health Program and the author or co-author of more than 100 journal articles and three books, including widely cited studies on medical bankruptcy and the high administrative costs of the U.S. healthcare system—who identifies a troubling trend:

Medicare and Medicaid are being privatized, essentially. Instead of paying doctors and hospitals directly, Medicare and Medicaid are increasingly subcontracting coverage to private insurers... That's enormously wasteful. There's a vast research literature that shows that's a much more expensive way of doing things than Medicare and Medicaid directly paying.

He explains that instead of Medicare and Medicaid paying doctors and hospitals directly, these programs now hire private insurance companies to manage payments, and that extra "middleman" layer adds a lot of cost, such as paperwork, administrative staff, and profit margins, which makes care far more expensive than if the government paid providers itself. Dr. David Himmelstein also emphasized:

The only route to change is going to be organizing American people to demand what they clearly want... We've overcome huge financial interests in the past in this country and done things that seem politically impossible, but it generally takes a large popular movement to do that..., We need to start preparing now for what comes after [current political challenges]... In healthcare, [Americans] are being ripped off by insurance companies and hospital conglomerates and are very much ready for change.

His statement underlines the urgency to pursue comprehensive reforms. A single-payer system, such as that proposed in various Medicare-for-All plans, is presented as the most comprehensive solution to overcome these inefficiencies. A universal system would consolidate bargaining power to negotiate lower prices, eliminate redundant layers of administrative bureaucracy, and remove the inherent conflict between profit generation and effective patient care.

Some critics argue that transitioning to a single‑payer system could require massive new revenue, as a Mercatus Center study found that Sanders's Medicare for All plan would cost $32.6 trillion over ten years, implying that income and payroll tax rates would need to more than double (George Mason University). The Congressional Budget Office also estimates that federal subsidies under an illustrative single-payer model would increase by $1.5 trillion to $3.0 trillion in 2030 compared to current law (Congressional Budget Office). Critics contend that such steep tax increases could dampen economic growth and cost middle-income households more than today's premium payments and out-of-pocket expenses. They also warn that limiting provider reimbursement rates to Medicare rates could lead to longer wait times and possible rationing of services (Congressional Budget Office)

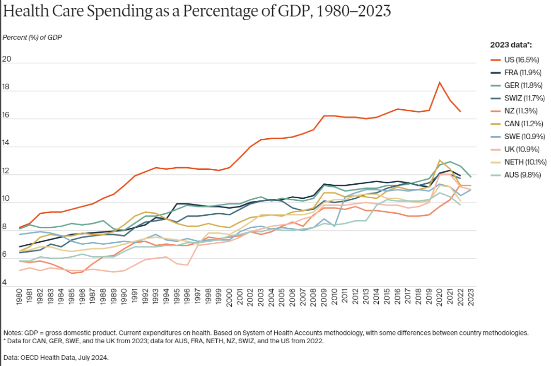

In addition, U.S. per capita health spending is projected to be $13,432 in 2023—exceeding that of any other high‑income nation and rising faster than in peer countries (Peterson‑KFF Health System Tracker; Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development) (Fig. 2). However, in comparable high‑income OECD countries, per capita health spending will average $7,393 in 2023, about half of what the United States spends per person (Peterson‑KFF Health System Tracker; Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development). Figure 1 plots each country's health‑system performance against its health‑care spending as a percentage of GDP: the United States sits alone in the bottom‑right corner—by far the highest spender yet the lowest performer among its peers.

In the United Kingdom, government-funded health care will cost £3,371 per person in 2019, or just 10.2 percent of GDP, yet the National Health Service provides universal coverage without excessive tax burdens (Office for National Statistics). Germany's statutory health insurance, funded by payroll contributions and general taxes, will spend about €5,699 per capita in 2020, or 13.2 percent of GDP, while experiencing slower real spending growth than the United States (German Federal Statistical Office). These international examples demonstrate that single-payer systems, when properly structured, can rely on reasonable tax rates while achieving lower overall health care costs and broader access to care (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development).

In conclusion, the transformation of the U.S. healthcare system into a single-payer framework represents not merely an economic imperative but a moral one. The evidence demonstrates how consolidated bargaining power, elimination of administrative redundancy, and realignment of healthcare priorities away from profit-seeking behavior could fundamentally restructure American healthcare delivery. This systemic change will require sustained grassroots mobilization to counter entrenched financial interests. The experiences of comparable nations affirm that universal coverage need not sacrifice quality or innovation, but instead can enhance health outcomes while reducing costs. Ultimately, the path toward equitable, efficient healthcare lies not in incremental adjustments to a fundamentally flawed system, but in bold structural reform that prioritizes patient wellbeing over corporate profit.

Works Cited

American Hospital Association. Uncompensated Hospital Care Cost Fact Sheet. AHA, 2017, www.aha.org/system/files/2018-01/2017-uncompensated-care-factsheet.pdf. Accessed 7 Apr. 2024.

Blahous, Charles. The Costs of a National Single‑Payer Healthcare System. Mercatus Center at George Mason University, July 2018, www.mercatus.org/publications/healthcare/costs-national-single-payer-healthcare-system. Accessed 4 Apr. 2024.

Blumenthal, David, et al. Mirror, Mirror 2024: A Portrait of the Failing U.S. Health System—Comparing Performance in 10 Nations. Commonwealth Fund, Sept. 2024, doi:10.26099/ta0g‑zp66. Accessed 12 Apr. 2024.

Ceron, Ella. "How Much Does It Cost to Have a Baby in the U.S.?" Bloomberg, 13 July 2022, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-07-13/how-much-does-it-cost-to-have-a-baby-in-the-us Accessed 6 Apr. 2024.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. "Historical National Expenditure Accounts." CMS.gov, 8 Jan. 2018, www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html. Accessed 11 Apr. 2024.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. "Negotiating for Lower Drug Prices Works, Saves Billions." CMS.gov, www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/negotiating-lower-drug-prices-works-saves-billions. Accessed 9 Apr. 2024.

Commonwealth Fund. "Paying for Prescription Drugs Around the World: Why Is the U.S. an Outlier?" CommonwealthFund.org, Oct. 2017, www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2017/oct/paying-prescription-drugs-around-world-why-us-outlier. Accessed 5 Apr. 2024.

Congressional Budget Office. Single‑Payer Health Care Systems: Selected International Examples. May 2020, www.cbo.gov/publication/56811. Accessed 10 Apr. 2024.

German Federal Statistical Office. "Health Expenditure in Germany." 2020, www.destatis.de/EN/Themes/Society-Environment/Health/Health-Expenditure/_node.html. Accessed 8 Apr. 2024.

Hsia, Renee Y., Y. Akosa Antwi, and Erika Weber. "Analysis of Variation in Charges and Prices Paid for Vaginal and Caesarean Section Births: A Cross‑Sectional Study." BMJ Open, vol. 4, no. e004017, 2014, doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004017. Accessed 6 Apr. 2024.

Kaiser Family Foundation. "Potential Savings for Medicare Part D Enrollees Under Proposals to Add a Hard Cap on Out‑of‑Pocket Spending." KFF.org, www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/potential-savings-for-medicare-part-d-enrollees-under-proposals-to-add-a-hard-cap-on-out-of-pocket-spending/. Accessed 3 Apr. 2024.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. MEDPAC, Mar. 2017, www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar17_entirereport.pdf. Accessed 11 Apr. 2024.

Office for National Statistics. "Healthcare Expenditure, UK Health Accounts Provisional Estimates." 2019, www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthcaresystem/articles/healthspendinguk/2019. Accessed 7 Apr. 2024.

Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development. Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, 2023, www.oecd.org/health/health-at-a-glance-19991312.htm. Accessed 8 Apr. 2024.

Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development. "Health Expenditure and Financing." OECD Data, 2023, https://data.oecd.org/healthres/health-spending.htm. Accessed 4 Apr. 2024.

Peterson‑KFF Health System Tracker. "Health Spending per Person in the U.S. Compared to Other Countries." 2023, www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/health-spending-u-s-compare-countries/. Accessed 10 Apr. 2024.

Santoro, Helen. "Health Insurers' Profits Are Reaching New Heights." Jacobin, Dec. 2024, jacobin.com/2024/12/health-insurance-profits-unitedhealthcare-aca. Accessed 5 Apr. 2024.

Vogler, Jacob. "Access to Healthcare and Criminal Behavior: Evidence from the ACA Medicaid Expansions." Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, vol. 39, no. 4, 2020, doi:10.1002/pam.22239. Accessed 12 Apr. 2024.

Woolhandler, Steffie, and David U. Himmelstein. "Single‑Payer Reform: The Only Way to Fulfill the President's Pledge of More Coverage, Better Benefits, and Lower Costs." Annals of Internal Medicine, vol. 166, no. 8, 2017. Accessed 9 Apr. 2024.

Younkin, David P. "Impact of Drug Price Controls on Pharmaceutical Innovation." Journal of Health Economics, vol. 76, 2023, article no. 102445, doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2023.102445. Accessed 3 Apr. 2024.